Posted

on Sat, Jan. 15, 2005

|

![]()

The fine art of fooling

fish with flies

![]()

![]()

Inquirer Staff Writer

![]()

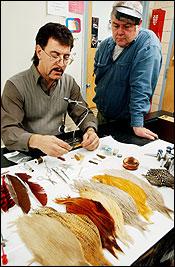

Pete Hoover

looked intently at his woolly bugger-to-be, just a size 6 hook held by a

vise and wrapped in black thread.

"Now

get a nice, long feather," Ed Emery instructed, holding one up for

show. "See the sheen on it? We talked about that last week. Tie it on

by the tip."

Hoover

selected a marabou - turkey under-feather, dyed black - and pressed it

against the hook's shank. A few windings of black thread secured it in

place.

To an

observer, the feather looked like nothing more than a clump of hair. To a

fish, however, it could form the tail of a leech or a crayfish wriggling

in the water. Food.

"Fooling

a trout on his terms," the teacher explained with the pride of a

fly-tying fly fisherman, "you have to go into his world."

This was

the last of six classes taught in the fall by the Main Line Fly-Tyers, a

club that takes tying flies as seriously as catching fish with them.

Another series begins next month.

Why tie a

fly?

"It

gives us something to do in the wintertime," said Emery, 50, who has

been tying his own for 15 years.

"Flies"

imitate bugs or other fish food, and an experienced tier can fine-tune

stores' standard patterns to reflect local variations.

"When

you catch a nice trout on a fly you tied yourself, it's really

satisfying," Emery said. "And some guys will say, 'I'm not even

going to fish this fly, I'm going to put it in a frame.' "

Hoover

signed up for the course largely because he was tired of spending a couple

of dollars on every fly, most of which is lost before drawing a fish. Bulk

purchasing of feathers, hooks and other materials cuts costs to about 25

cents apiece. An experienced tier can dress a fly in under a minute -

after years of practice.

Good fly

fishing requires thorough knowledge of the biology of predator and prey,

and how they interact as seasons and water conditions change. Faced with

thousands of possibilities, an angler must know which fly to choose at any

given time and place; how the fish would expect it to behave above, on or

under the surface of the stream; and how to give it action - to make the

knot of thread and feathers and hair come alive.

The woolly

bugger is easy to learn, and its striking underwater movement seduces a

variety of fish. Dozens of variations are employed.

To make a

basic black-and-olive bugger, Hoover clamped a fly-tying hook in a

fly-tying vise and wound some black thread around the shank. Next came

wraps of thin lead wire, secured by a few windings of the thread. The lead

causes a woolly bugger to sink head-first, then rise in an undulating

motion as an angler strips the line in short retrievals.

In a

laboratory mimicry of metamorphosis, a "fly" began to form among

the alternating layers: marabou feather for the tail, saddle hackle

(feather from a rooster's back) to suggest legs or gills moving in a blur,

olive chenille for color, black thread wound around and around near the

end of the hook to hint at a head and secure the whole shebang.

The same

basic wrapping-and-layering technique is used for all flies, many of them

far more complex. Only the materials change.

Hoover had

worked quietly all evening. Now the environmental consultant from

Lafayette Hill, Montgomery County, showed some of the eight flies he'd

learned to tie as Emery's only pupil. (A half-dozen others learned more

advanced techniques from a teacher across the room.)

"That's

a hard one," he said, pointing to a tiny deer-hair caddis - a club

specialty - whose tan rabbit fur, black-and-brown deer hair, and brown

rooster hackle were tied to imitate an adult insect lighting on the

water's surface to lay eggs.

Hoover, 37,

fly-fished with his father as a child but gave it up because all of his

friends had spinning rods. He came back five years ago, appreciating the

challenge yet still buying the flies.

"I

never realized how much went into it," he said, vowing to practice

through the winter and upgrade his skills in the Main Line Fly-Tyers' next

course. "I'll be really happy when I catch a trout on one of

these."

As class

ended, he offered up his woolly bugger for appraisal.

"It's

a little long," Emery said. "But you know what? It will go like

crazy in the water."

Contact staff writer Don

Sapatkin at 610-313-8246 or dsapatkin@phillynews.com.